Issue No. 3

Common Daisies

Hi friends,

Happy May full moon!

This month I’ve written about common daisies—and a baby squirrel named Chuck.

Thanks for having me in your inbox. Hope to hear from you.

x Jill

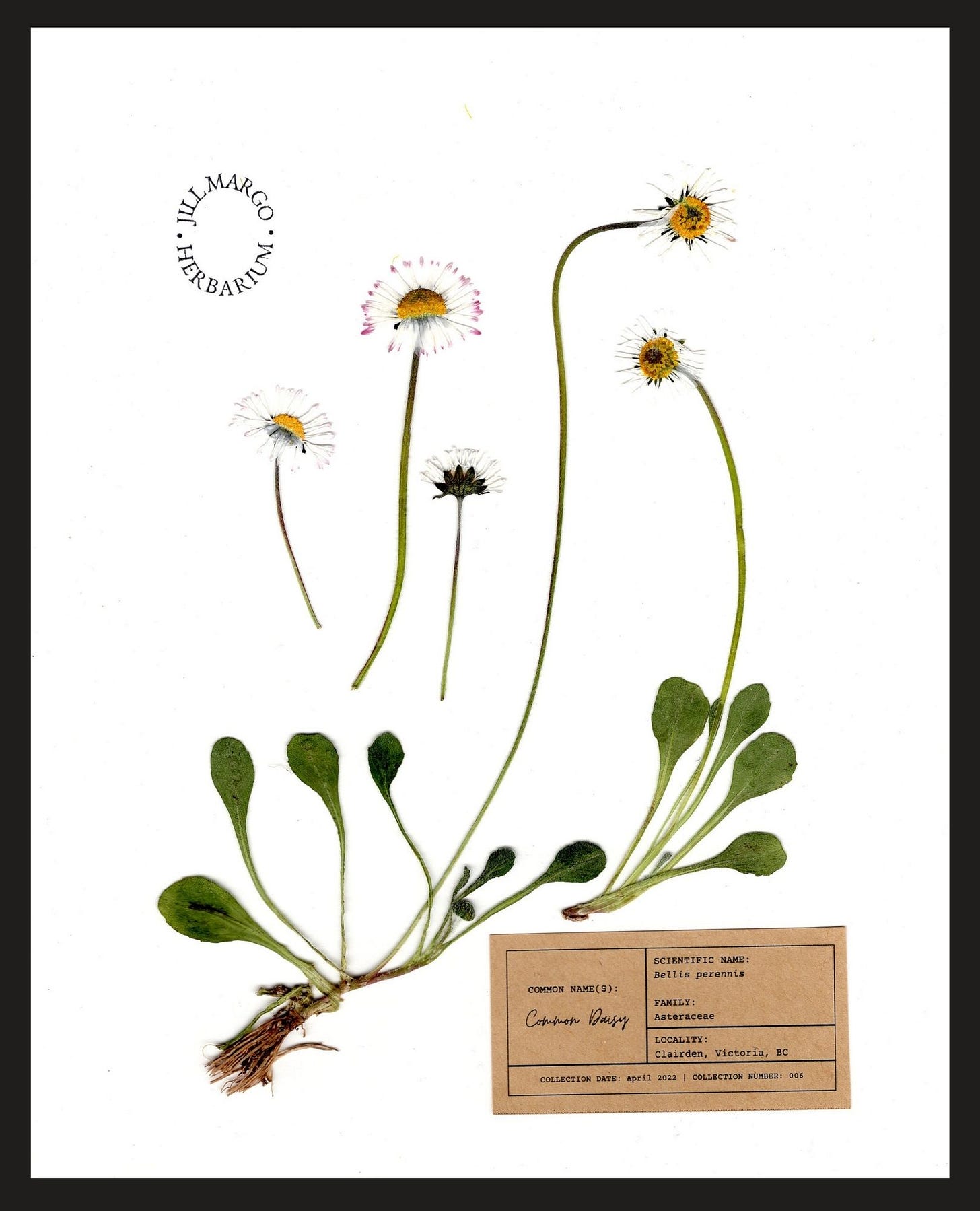

006 | Bellis perennis (Common Daisy)

A grey squirrel has been nesting in a hollow in one of our slenderer oak trees—the one with the hedge growing around it, next to the rhodo that’s the colour of Hawaiian Punch. Only about ten or twelve feet up, the hollow slants downward like a jaw dropped in surprise, so at the right distance, it’s possible to see into its mouth. A. noticed the nest a few weeks ago and pointed it out to me when we were saying goodnight to the garden during the blue hour that comes after sunset, before it’s fully dark. I could just make out the shadowy forms of twigs and dried leaves protruding from the hollow. There used to be a drey high up in the branches of the oak across the lane. We’d noticed recently that it was gone and so we wondered if we were looking at a replacement nest, or at least an auxiliary one. A couple days later, we began to see Strange Squirrel going in and out of the hollow.

We called her Strange Squirrel because she was new, Nutty and Fluffernutter being are our usual backyard squirrels. Soon, however, we began calling her Mama Squirrel because it was clear she was protecting her offspring in the den. It was thrilling to see the swish of her tail—like the train of a gown or bottom of a floor-length cape—disappear into the hollow and to imagine her little ones (or one, since squirrel litters vary from one to nine) safely tucked inside. Sometimes, if I stood on my tiptoes underneath the tree, I could see her little face peering out of the nest with alert ears and Glosette eyes.

This afternoon, I was visiting with Betty-Ann at the picnic table, while Mama was busy collecting acorns, skittering up and down the oak, going in and out of the hollow. She seemed aware of us, but not much bothered. Then A. joined us and Julian stopped by to pick something up and we all watched Mama doing her busywork, which, come to think of it, did seem a little more frenetic than usual—like something was up. We discussed whether our presence might have been bothering her after all, but it was hard to take our eyes off her. Had we, we wouldn’t have seen what came next: Mama braced herself on the lip of the hollow, then reached in and, to our amazement, with some effort, pulled out a well-developed, white-bellied, fluffy-tailed kit in her mouth.

When squirrels are born, they’re blind, deaf, pink, furless and so tiny that half a walnut shell could serve as a bassinet. Mama’s baby—Chuck, as A. immediately named them (and whose sex is unknown, so will be referred to with the pronoun “they”, as per Dr. Jane Goodall’s guidelines)—looked almost too big for her to carry in her mouth, which means, according to my research, they’re at least ten to twelve weeks old. She held the kit up on that threshold like they’d just been found out for doing something naughty, and I wondered if we were witnessing the moment that Chuck was getting chucked out of the nest. But then Mama turned and stuffed Chuck back into the den, which clearly took brawn and involved some chittering from both. Or maybe I read it wrong. Maybe it was us who were in trouble for gabbing too loudly and Mama showed us Chuck as a way to say, “Hey, I’ve got a kid in here and a headache, so give us some peace.”

Betty-Ann, then Julian, left soon after that and A. and I went back inside, still awash with wonder. At one point outside, the adorableness we witnessed had made me look like those young women you see in old photos who were experiencing Beatlemania (screaming—albeit silently, in my case—and clutching their heads). Later, I took my basket out to collect daises from the boulevard on the other side of our back fence, close to the foot of Mama and Chuck’s oak. I like this strip of land because it has the lovely scruffiness of a meadow with its dandelions, chickweed, Spanish bluebells, orchard grass, rough bluegrass, vetch, clover, and other plants. The daisies are what you notice the most right now though—stands and swathes of bright white and yellow against the vibrant thrum of green.

Floriography (the language of flowers) was popularized by the Victorians and as such, a lot of flower meanings need a serious update (you know, so they’re not rooted in a repressive, white supremist, patriarchal culture). Still, enduring floriography tells us that, for various reasons—including an association with Freya, Norse goddess of love, beauty, and fertility—daisies represent motherhood, babies, and innocence, which is a nice connection when thinking about Mama and Chuck. It's also the reason that I went to collect daisies in the first place—because I’m making a pressed flower composition to hang in the nursery of our friends’ newborn. Baby E. was born in April and daisies also happen to be the flower for that birth month.

I was bending over picking stems, thinking about all this, when a sprightly (much more so than me), elderly, heterosexual couple in windbreakers walked by. The woman caught my eye when I stood up and asked: “Are you picking anything interesting?”

“Just daises,” I replied and immediately felt guilty for saying “just”, a word that felt diminishing. Why had I said it?

When something is commonplace, abundant, and free, we tend to devalue it, which, unfortunately, isn’t very honouring to the generosity of that thing. What’s more, the ordinariness of that thing can make us stop seeing it and being amazed by it. Maybe I had said “just” because I felt that any exuberance over an underfoot “weed” would be seen as odd.

When one turns one’s attention deeply to an “ordinary” daisy though, and begins to study it, one discovers they’re not so ordinary. For example, daisies, one of the first flowers a child is able to draw because it looks so simple, are actually complex in design. They are “composite flowers”, meaning that they consist of two flowers combined into one. The inner section is called a disc floret and the outer section is called a ray floret. If you look at the disc floret—the sunny yellow centre—with a magnifying glass or hand lens (as I did), you’ll see that it is reminiscent of one of those pink or blue Liquorice Allsort jelly buttons (or “spogs”), covered in teeny, round sprinkles (or “nonpareils”, although, when it comes to daisies, the balls are really tube-shaped florets, which is more evident when they open). If we were to imagine a disc floret done in beadwork to this design, we would call it meticulous and exquisite.

Daisies, like humans, have circadian rhythms and are diurnal. At first light, the ray floret—whose petal tips may or may not have a blush of reddish-pink—opens, and when it is dark the ray floret closes. This behaviour is called nyctinasty and is so that the plant can sleep and rest and protect its pollen from “nectar robbers”, insects that remove pollen without causing pollination. For this reason, in Old English, daisies used to be referred to as “daes eage”, meaning “day’s eye”, which evolved into the name daisy. The expression “fresh as a daisy” means to have slept well and woken refreshed (and does not have anything to do with personal hygiene, despite the expression still being misused in the marketing of maxi pads, douches, deodorants, and so on—but that’s a whole other essay).

When Mama held up Chuck we got to see something that is normally unseen, which made it extraordinary. Daisies, on the other hand, are highly visible, but it doesn’t mean that they’re not extraordinary too.

I’m thinking now of M. who is one of the best writers I know, but who doesn’t identify as a writer. She wrote to me after her father—whom I adored too—died, years ago now, and described the action of his death as “not a candle going out, but the light of a lantern being carried by a traveller, flickering as he moves further away and then finally lost around a bend that you cannot see.” She then said, “It was as simple and vast and impersonal as a baby being born.”

I’m not sure exactly why I’m thinking of these words right now, but I think it has to do with the line “as simple and vast and impersonal as a baby being born”. When M.’s father slipped away, she saw that what was extraordinary to her experience was also ordinary in the grand scheme of things. I think that’s it—that’s what I’m trying to say too, that in the extraordinary (Mama and Chuck) there is the ordinary, and in the ordinary (common daisies) there is the extraordinary. Ever was it so and ever may it be.

Beautiful and inspiring imagery, Jill. Loved the eyes like glossettes...and the comparison to jelly buttons (I just ate some of those yesterday!) I, too, love the daisy and the seeming simplicity. In fact, I just wrote in my "bones" journal last Tuesday about daisies and the act of making daisy chains when we were younger. And Chuck...ahh.... This was the lovely little read that I needed this afternoon.

I love your expressions of awe-in-nature, which is my own state of being. (It is what sustains me now, during our Great Horror of concurrent nastiness.) ALSO, I love that you quoted your friend who doesn’t self-identify as a writer. I want to hug the whole big ball of loveliness that is this essay!